The Dutch government has announced that Europe will need at least five years to achieve independence in artificial intelligence (AI) development, according to statements from State Secretary Zsolt Szabó (Digitalization). This timeline emerges as Dutch public sector organizations gain expanded permissions to implement AI solutions, with a preference for European-developed systems[1]. The policy shift reflects growing concerns about geopolitical dependencies and the need for sovereign AI infrastructure capable of meeting both innovation and security requirements.

Strategic AI Infrastructure Development

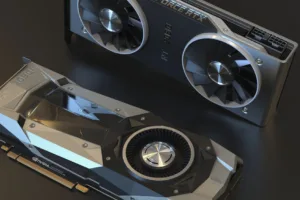

The EU’s €20 billion InvestAI initiative under the AI Continent Action Plan forms the backbone of Europe’s push for technological sovereignty. The Netherlands is establishing an “AI Facility” targeting healthcare and robotics applications by 2025[6]. Current negotiations with hardware manufacturers like NVIDIA and AMD aim to secure the physical infrastructure needed for domestic AI development. This infrastructure plan addresses critical security considerations, particularly regarding data residency and supply chain integrity for AI systems used in sensitive government functions.

From a security operations perspective, the transition period creates unique challenges. Organizations must evaluate the trust boundaries between existing international AI services and emerging European alternatives. The five-year timeline suggests interim measures will be necessary to bridge capability gaps while maintaining security standards. Technical teams should prepare for phased migrations that account for model validation, data pipeline adjustments, and monitoring system recalibration.

Regulatory Framework and Security Controls

The EU AI Act establishes binding requirements for high-risk AI applications, with specific provisions affecting security implementations. Real-time facial recognition remains prohibited except for counter-terrorism operations, while private sector scoring systems face fewer restrictions[150], [229]. The Dutch Data Protection Authority (AP) is expanding its oversight capabilities to enforce these regulations, creating new compliance requirements for AI deployments in both public and private sectors.

Municipal applications demonstrate the tension between operational needs and privacy concerns. Amsterdam’s use of facial recognition during Koningsdag celebrations has sparked debate, particularly regarding data retention policies and algorithmic transparency[9]. Professor Boutellier of VU Amsterdam emphasizes the need for human oversight mechanisms in such public-order applications, suggesting layered approval processes and audit trails as technical safeguards.

Security Considerations for AI Implementation

The Dutch approach highlights several security-relevant aspects of AI adoption:

| Domain | Security Consideration | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Public Safety | AI-driven crowd monitoring requires strict access controls and logging | Utrecht’s Vrijmarkt footfall analysis |

| Healthcare | EHDS compliance for diagnostic AI systems | Exscalate4CoV drug discovery project |

| Critical Infrastructure | Supply chain verification for AI components | AI Factories initiative (15 planned sites) |

Cybersecurity teams should note the emerging patterns in AI-related threats. Europol has documented cases of AI-powered disinformation campaigns, while ENISA warns of vulnerabilities in autonomous transport systems that could be exploited through compromised AI components[160], [255]. These threats necessitate robust model validation frameworks and runtime monitoring for AI systems in security-sensitive roles.

Operational Recommendations

For organizations transitioning to European AI solutions, several technical measures can mitigate risks during the five-year development period:

- Implement model provenance tracking for all third-party AI components

- Establish separate monitoring pipelines for AI decision outputs

- Conduct regular red team exercises against AI interfaces

- Maintain air-gapped fallback systems for critical functions

The Dutch Gemeentewet (Municipal Law) Article 172 defines public order as “the orderly course of community life,” providing legal context for AI applications in public safety[Bijlage 2]. This definition becomes operationally relevant when configuring AI systems for crowd control or urban management, requiring security teams to align technical controls with legal interpretations of public order.

As Europe works toward AI independence, security professionals face the dual challenge of maintaining existing systems while preparing for sovereign alternatives. The five-year transition period offers an opportunity to develop robust security frameworks tailored to European AI ecosystems, provided organizations allocate sufficient resources to parallel development and hardening efforts.

References

- “Kabinet: Europa heeft minimaal 5 jaar nodig om onafhankelijk te zijn op AI-gebied,” NU.nl, 2024.

- InvestAI initiative documentation, EU AI Continent Action Plan, 2024.

- Koningsdag AI surveillance reports, Amsterdam Municipality, 2024.

- EU AI Act, Article 150 – Real-time biometric identification restrictions, 2021.

- Europol report on AI-driven disinformation, 2021.

- EDPS statement on public-order AI applications, 2024.

- Digital Twin Cities pilot program documentation, 2024.

- EU AI Act, Article 229 – Private sector scoring provisions, 2021.

- ENISA threat assessment for autonomous transport systems, 2021.

- Burgemeester Bruls (Venlo) interview on AI ethics, Bijlage 1, 2024.

- Dutch Gemeentewet (Municipal Law), Article 172, Bijlage 2.